The term “stylist” is shrouded in mystery and allure, a concept that has ignited endless debates among writers and readers. Despite its charm, it carries a heavy burden. For those who venture into writing or feel its pull, it can provoke intense psychological struggles: burnout, inferiority complexes and even deep-seated depression.

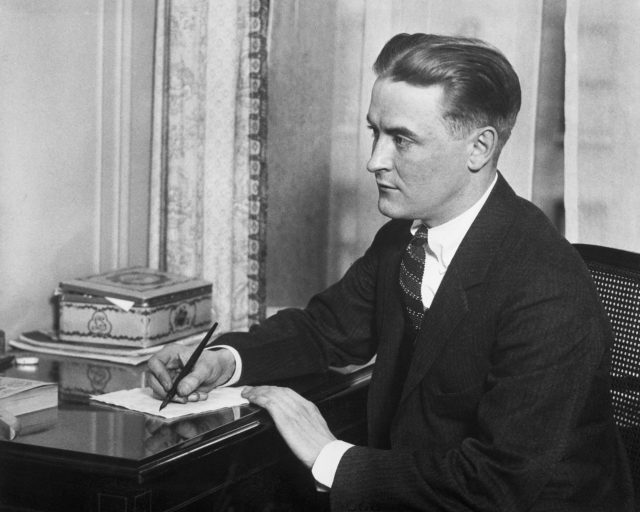

In 1925, F. Scott Fitzgerald ascended to literary greatness with “The Great Gatsby.” His language, his storytelling – it was nothing short of spellbinding, propelling him to international fame. Yet, the very style that lifted him to such dizzying heights soon became a double-edged sword. When he sought to recapture that same magic in later works, he faltered. The brilliance that once burned so brightly began to dim, leaving him grappling with a sense of failure and financial despair. Fitzgerald’s story is a haunting reminder of how the very style that can elevate a writer to celestial heights can just as easily bring them crashing down – a narrative that is as poetic as it is unsettling.

Philologists, those who study the very essence of language, insist that concepts shaping our lives must be defined with precision. To them, every dramatic event is anchored in a concept, and even if such a concept doesn’t yet exist, it must be birthed into language. The goal is to illuminate our understanding, to see events as clearly and accurately as possible. But this raises a daunting question: Who, then, has the authority to define “style”? More pointedly, who can decree who is truly a “stylist”?

The answer is simple: a voracious reader. But not just any reader will do – this reader must possess a refined palate and a wealth of knowledge. Imagine a reader who has devoured thousands of books, one who is steeped in literary history, and who understands the nuances of aesthetics. How rare such individuals are! The concept of “stylist” is a fragile, delicate thing –so much so that even defining it demands a person of exceptional discernment. It is this discerning reader who holds the power to bestow immortality upon a writer.

But this almost mystical concept isn’t confined to the realm of literature alone. It permeates the world of music, too, where it emerges as an unforgiving standard. Composers, virtuosos, conductors – all have been put to the test by this relentless notion, creating an atmosphere of fear that could be straight out of a Tim Burton film, where the shadows are long and the sense of dread palpable. Artists, desperate to carve out their place in history, are known to shudder at the mere thought of it. The entire ordeal is nothing short of spine-chilling.

Yet, there are those who manage to escape this stifling grasp. Consider Joaquin Rodrigo, who, at the age of 38, composed “Concierto de Aranjuez” in 1939, and in doing so, shattered the icy grip of stylistic expectations, establishing himself as a force to be reckoned with. Maurice Ravel similarly broke through when he introduced “Boléro” to the world of ballet, securing his place as a “stylized artist” in the eyes of the authorities. Richard Wagner would only achieve such recognition after the monumental creation of “The Ring Cycle,” his epic four-opera magnum opus.

But not everyone escapes unscathed. Franz Schubert, who died at the tender age of 31, was a man tormented by the curse of “style.” Though today he is venerated as one of the greats of his time, Schubert spent his final days in a relentless cycle of self-doubt, mercilessly questioning his worth as an artist.

His reflections on this struggle are etched into his work, particularly in the sorrowful strains of “Winterreise,” where the echoes of his inner turmoil still linger.

Signature of the mind

In this context, it’s clear that style is far from being just a superficial embellishment in writing or composing. Rather, it’s the very essence of how we articulate our thoughts and connect with the world around us. Style is deeply woven into the fabric of our expression, shaping the way we convey ideas, emotions and perspectives. Each writer, composer or speaker leaves behind a distinctive stylistic fingerprint – a blend of syntax, diction, tone and rhythm that sets their work apart from others. This uniqueness isn’t merely a matter of taste; it’s an outward manifestation of their innermost worldview, much like a signature imprinted on every piece they create. Style transcends mere technique. Georges-Louis Leclerc, known as Count de Buffon, famously encapsulated this idea in his epigram from “Discourse on Style,” where he asserted, “Le style est l’homme même” (“Style is the man himself”). Similarly, Arthur Schopenhauer likened style to “the physiognomy of the mind,” suggesting that it reveals the very nature of one’s intellect and spirit.

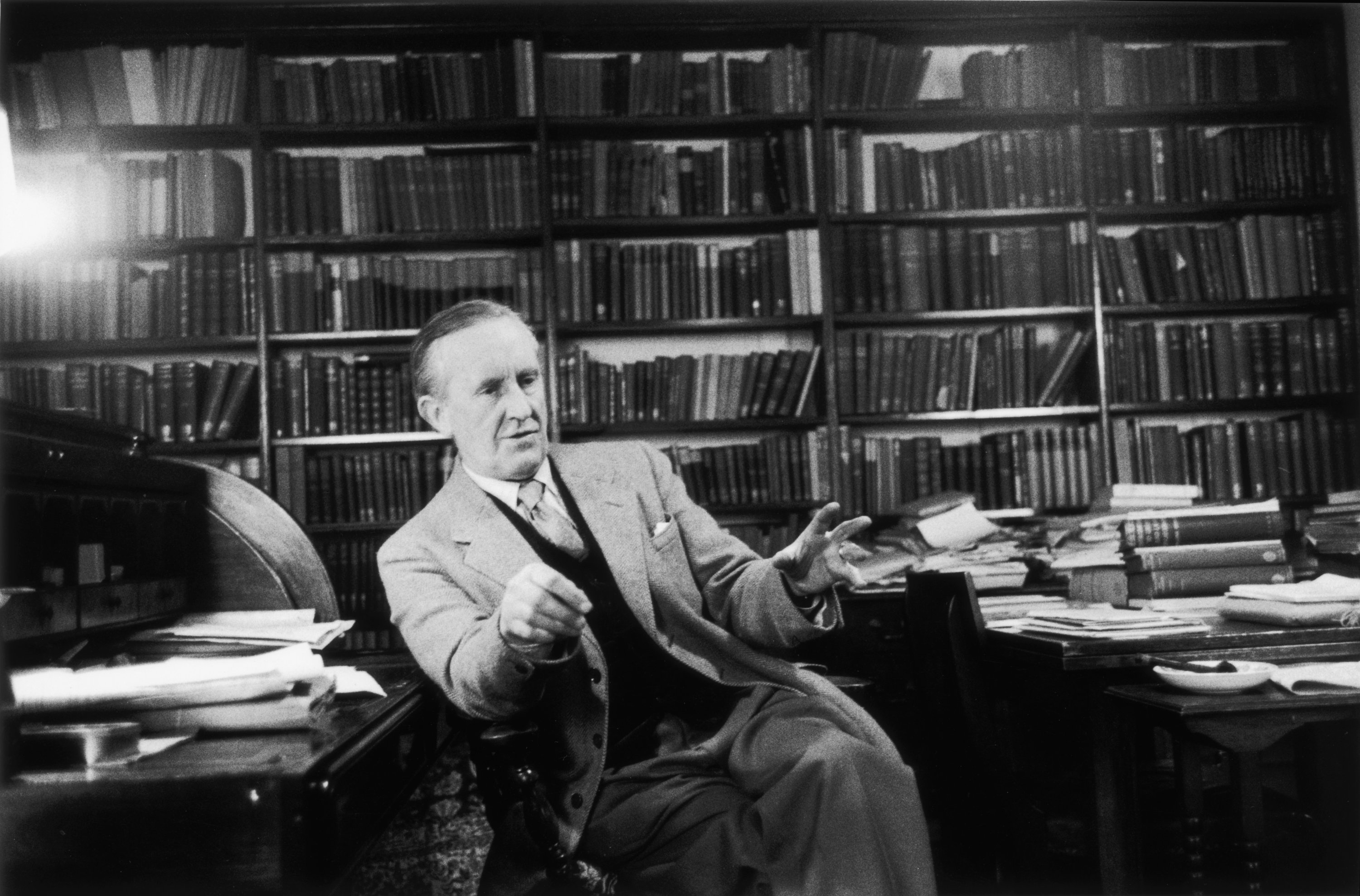

Consider the literary giants Thomas Mann and J.R.R. Tolkien. Mann’s prose, a labyrinth of philosophical inquiry and introspection, mirrors his own contemplative and probing mind. His words are not just sentences; they are pathways into the depths of human existence, each carefully constructed to lead the reader through complex ideas and emotions.

Tolkien, on the other hand, crafts an expansive universe filled with elves, orcs and epic quests. His style is a direct reflection of his boundless creativity and his deep love for mythology and language. Through their unique styles, both Mann and Tolkien offer readers a window into their souls.

History in brief

Stylistics is a journey through time, rooted deeply in the minds of the Greeks. It all began with Aristotle’s “Rhetoric,” a work that laid the cornerstone of persuasive style by dissecting ethos, pathos and logos – the trinity of rhetoric that continues to influence how we sway minds and hearts today. In the ancient world, rhetoric wasn’t just a tool; it was an art, a powerful force that could shape societies by guiding public opinion and thought.

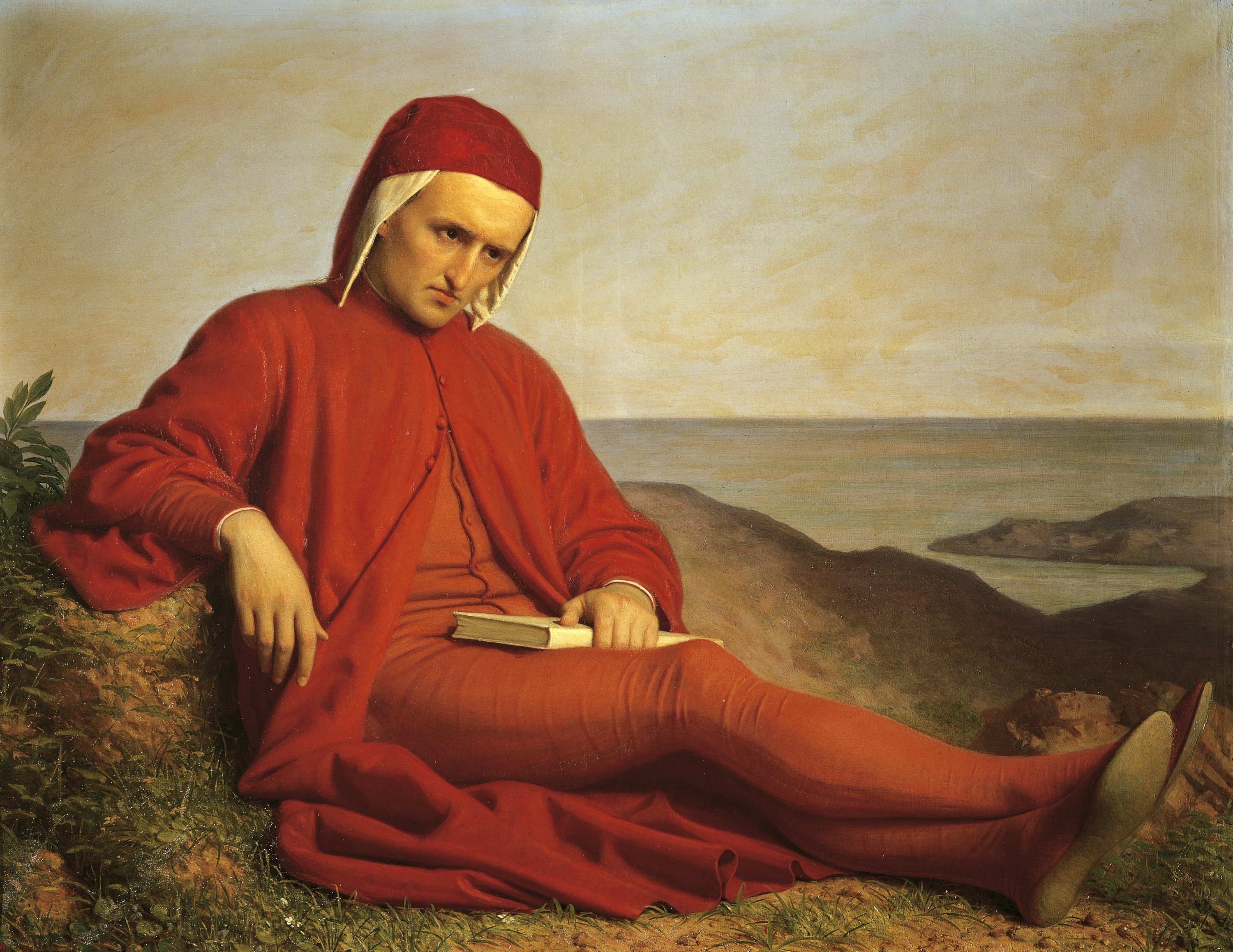

As the world moved into the medieval era, stylistics became a bridge between theology and philosophy. The power of style was harnessed by thinkers like Dante Alighieri, who, through the verses of “The Divine Comedy,” not only told a story but wove together spiritual and philosophical ideas.

The Renaissance, with its revival of classical ideals, brought stylistics into the realm of the individual. Figures like Erasmus championed a style that was clear, elegant and reflective of personal expression. This era marked a departure from the collective voice of the medieval period, celebrating instead the unique perspective of the individual. Style became a mirror of the self.

With the Enlightenment, the focus shifted once more, this time toward clarity, reason and the precision of thought. In this age of reason, style was scrutinized for its ability to convey ideas with exactness and logic. Writers like Voltaire and Jonathan Swift exemplified this approach, using their sharp, clear prose to engage in the social and political debates of their time.

But as the world moved into the Romantic era, stylistics transformed yet again, this time embracing the power of emotion and the individual’s inner world. Writers like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Lord Byron broke away from the rigid structures of Enlightenment clarity, instead using style to explore and express the depths of personal feeling. The Romantic era celebrated the subjective, the passionate and the unique. Style became a conduit for the raw.

The 20th century brought with it a new wave of change as stylistics merged with literary theory. The rise of structuralism and post-structuralism challenged traditional notions of style, viewing it not just as a tool for expression but as a force that shapes meaning itself. Scholars like Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault examined the ways stylistic choices influence how texts are perceived and how they construct the reality around us. In this era, style was dissected, analyzed and reimagined as a dynamic component of meaning-making, one that interacts with the reader’s mind to create layers of interpretation.

Sonnet and tweet

Today, stylistics is a multidisciplinary field, blending literary analysis with linguistics and psychology. It examines how style influences meaning, identity and communication across various media. The digital age, with its emojis, memes and internet slang, has introduced entirely new dimensions to stylistic expression, reflecting the rapidly evolving ways in which we communicate in a connected world. Today, stylistics isn’t just about literature; it’s about understanding the nuances of communication in all its forms, from a Shakespearean sonnet to a tweet.

So, after weaving through the tangled threads of style, we arrive at a truth as sharp as Occam’s razor: style, that esoteric chameleon, is nothing more than a mirror. A mirror that, when polished, reflects the soul of the creator – yet, when cracked, turns into a hall of illusions, distorting every effort to recapture the lost magic. The pursuit of style is a thrilling, nerve-wracking game of Russian roulette, where each spin of the chamber could lead to literary immortality – or the silent fade into obscurity.

In the end, perhaps the ultimate style is not in the flourish of the pen or the bravado of expression, but in the quiet confidence to leave the stage before the curtain falls. After all, not every play ends with applause; some stories are meant to linger in the air, unresolved, like an unfinished symphony.